Although both candidates for U.S. President talk interminably about government spending and deficits, taxation, health care and global warming, neither one says much about the Employee Free Choice Act, a proposed federal law that would greatly ease union organizing efforts. EFCA would allow “card check” unionization, whereby a company would automatically be unionized if 50% plus one of its employees sign union authorization cards, avoiding the secret-ballot voting process that federal labor law currently requires.

This essay answers nearly 120 executives from ferrous and nonferrous foundries and diecasters who contacted me after our March 2007, FM&T report, “Foundries Fearful of New Unionization Drives.” They asked what they should do now, to avoid the future risk of unionization should this legislation pass. Readers also may request a 10-question survey to assess their company’s vulnerability to unionization.

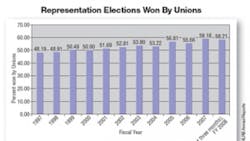

Overall, in FY2006 unions won just over 58% of secret- ballot elections, continuing a decade-long unionization trend in which labor interests won a rising percentage of elections (See Fig. 1.) In primary metal manufacturing, there were 38 elections in FY2006, 18 of which (47%) were won by the management side. That margin is lower than the national average, but still … the 20 foundries that “lost” affiliation drives/elections are now saddled with a union (see Fig. 2.)

The new law

One of the main provisions of the new law requires the National Labor Relations Board to “certify” a union at a company if the union obtains “authorization cards” from just over 50% of its employees – and with no election. This means that a company could be unionized without warning by a surreptitious “card check” campaign, without any opportunity to mount a counter-campaign.

Under current labor laws, if more than 30% of a foundry’s workers file union-authorization cards with the NLRB, the board orders an election to be held fairly quickly. Between the filing and election, both unions and employers have about one month to campaign, using their First Amendment rights to persuade workers how to vote.

Employees vote whether they want union representation, in elections strictly supervised by the NLRB. They vote secretly, in voting booths, so nobody knows how any individual voted. The winning side is the one for which a majority of the votes has been cast. Votes like this, and the run-up campaigns that precede them, would be eliminated by the new EFCA legislation.

Many foundry executives say they are unworried about unionization efforts because their operations are small; they “know” their workers, many of whom are longtime employees who are “like family.”

In reality, just over 70% of all union elections occur in plants with fewer than 50 employees (see Fig. 3.) Small foundries or large corporations with numerous small, casting plants are thus highly vulnerable.

Statistics also show that unions have two favorite targets. First are smaller companies with under 50 workers whose busy owners rely on a trusted foreman to run the shop in an informal fashion. The other are those companies with high percentages of ethnic minorities, for historic reasons (see “Managing the Hispanic Worker,” FM&T, February 2004.) Unless some workers trust management well enough to alert them to a stealth card-signing campaign underway at locations like these, a company may have no chance to present its case to persuade employees not sign the cards.

Preventive measures

To prevent unionization, foundry executives must ascertain what their workers think about their employer, and why they think that way. Because they will be the ones who decide whether or not to sign union cards, the workers’ perceptions are the employer’s reality. Unless employers objectively identify and correct what irritates their employees, under the proposed new law a union’s stealthy card-signing campaign will mean virtually automatic unionization.

Broadly speaking, there are three areas of danger in metalcasting operations. Any of them can trigger a successful unionization drive. (Contact the author for a detailed self- assessment that will help you explore these danger zones in depth.)

Supervisory behavior — Unfair supervisory behavior is the most important reason that employees seek out a union. If workers believe supervision is not “fair,” then the company is not considered fair --the all-important predictor of union vulnerability. But evaluating supervisory behavior isn’t that easy: Complaints about unpopular supervisors are often dismissed with the off-hand statement that “workers dislike him because he makes them work.” Not so. Indeed, foundry employees expect to work but greatly resent supervisory behavior they view as favoritism.

Giving a supervisor the sole responsibility for work assignments, for deciding who is hired/fired, who receives overtime assignments, who is laid off, or who is disciplined with no appeal, simply increases a foundry’s vulnerability. For example, a supervisor may reasonably want to give a worker overtime “because he can rely on” or wants to reward that person. Other employees view this as preferential treatment, or worse. “Open door policies” usually are ineffective because most employees are afraid to complain.

In the case of a Spanish-speaking workforce, a supervisor’s job is harder because the language and misunderstood cultural barriers create greater opportunity for either side to misinterpret actions or decisions . Foreignborn Spanish-speakers generally accept being ordered around without explanation; as far as they’re concerned, that’s the supervisor’s job. Authority is accepted, but perceived abuse of it is resented. Any perception that a supervisor “plays favorites” is an opening argument for union organizers – just what a union contract will prevent, they claim. If the supervisor raises his voice to workers or calls them names—or bellows, “Hey, this ain’t a country club!” — this is especially resented. That is the way animals are treated in Mexico and Central America.

In many smaller foundries, owners often rely on a bi-lingual foreman or shift supervisor, giving him sole responsibility for hiring/firing, making work assignments, and taking disciplinary actions from which there is no appeal. Much better would be a set of simple company policies that provide a structured work environment, communicated to and understood by all, and viewed as fair.

Management communication efforts — Frequent contact with the company owner or president is important to all employees. Periodic meetings with the workforce, stopping to chat with individuals on the plant floor, or attending employee events on occasion ( e.g., inexpensive lunchroom birthday or service awards parties) are gestures that workers appreciate, especially minority workers, and are most helpful to a company that wants to retain its non-union status.

First, regular and friendly direct contact establishes a personal connection that encourages employee loyalty– a valuable defense against outsiders’ influence. Second, workers are gratified that they know who it is they work for, rather than simply being subject to impersonal work rules and foreman’s vagaries. (This is especially true for foreign-born employees who may not automatically identify with the capitalistic enterprise.)

Owners of smaller metalcasting firms need to ascertain how their communication efforts are perceived by their workers, and if they fall short of employees’ expectations. If they are found to be inadequate, remedial action should be taken.

Use of seniority in workplace decisions — It has become common for employers to rely on “merit pay” and pay-for-performance guidelines, rather than on a reasonable recognition of seniority in pay and bonuses, layoffs, and overtime. Most smaller firms understandably say they cannot afford to honor strict seniority, especially in daily decisions on short-term layoffs, and overtime assignments almost always are made in a hurry. Many foundries say, “We don’t have seniority, and don’t want to … That’s exactly why we don’t want a union.”

Again, owners of smaller foundries managing like this are again providing union organizers with an open invitation. They dangerously ignore the value system of their unskilled or semi-skilled workers who strongly believe in seniority “rights,” because time on the job is all they have. Workers want management to recognize seniority in the work environment in some way. It behooves owners to re-think the strict “merit” approach for raises, promotions, work assignments, and layoffs.

Compounding this danger is the fact that owners often rely on the foreman to make the “merit” recommendations or overtime assignments. With no guidelines to follow, foremen often recommend their pals and drinking buddies for raises or plum assignments. Such situations cry out “favoritism” to the workers, and is just the sort of behavior organizers say would be prevented a union contract.

Assessing your vulnerability to unionization involves more than listing these three danger areas. To gain a more precise understanding of your situation and how to improve it, take the 10-question self-assessment to explore and evaluate your vulnerability to unionization.

Mariah DeForest is a partner in Imberman and DeForest Inc., a management consultant group that specializes in subjects relating to manufacturing employment, including employee productivity, supervisory training, Gainsharing, and other pay-for-performance programs. For a copy of the 10-question self-assessment mentioned in this report, or to read other reports cited here, contact the author at [email protected]