In the previous articles of this series we addressed the tough competitive environment of the U.S. foundry sector. We’ve also set the stage for discussing growth strategy using the concepts of: Core Business, Adjacencies, and Opportunity Mapping. In this article we explore in greater detail how these concepts can be applied to a foundry business to map out strategies leading to long-term sustainable and profitable growth.

The Core and Adjacencies — The core is best described as whatever process or function provides the most unique and greatest competitive advantage for the company in the marketplace. Many foundries try to identify their core business internally, based almost entirely on process and metallurgical capabilities. Usually this is a mistake, unless the foundry can honestly say that they have a unique process or metallurgical capability from which they derive more than 80% of their profitability.

Perhaps one example of a foundry with unique process capabilities might be the investment caster Signicast. Their commitment to automating and yet keeping the investment casting process highly flexible has given them a commanding lead in the general industrial investment casting market.

An example of a company that has extraordinary metallurgical capabilities as its core is Belmont Metals Inc., of Brooklyn NY, which manufactures over 3,000 non-ferrous alloys and pre-shapes that go into a wide variety of industries and applications.

Some attributes that are not ‘core’ but seem to be high on the list for foundries are:

• Foundry age. While being in operation for a hundred years, or three generations, is admirable (and might mean there is in fact a strong core) being in business for a long time is not a core attribute.

• Highest quality, fastest turnaround, lowest “total” cost, best website, and on and on. Unless you can very confidently demonstrate that this is critical to deriving 80% of your profits, don’t fool yourself. Usually these attributes are just the cost of admission to do business.

Identifying the business core is best done with an external focus. Are there a small number of customers that provide 80% of the profitability? Or, perhaps there is a particular type of casting that makes up the 80%. Perhaps there is one particular market segment, or better, a niche within a market segment, that provides 80% of the profits. Possibly you might identify a set of competencies, such as unique casting design capabilities, combined with process capabilities, as the true core. Historically, geography – say, a 200-mile radius of the foundry -- has been important in defining a foundry’s core business. However, the chances of maintaining a core business based on geography today are decreasing, quickly.

It is intellectually challenging for most companies to accurately define the core business. But, once that objective is completed, it’s amazing how much easier it is to find, prioritize, resource, and manage growth in adjacencies.

Adjacencies — Adjacencies are potential new business areas that in some way build upon and leverage the core. Ideally, pursuing growth in an adjacency also strengthens the core by making it even more unique. Strengthening the core is also a desirable and often realized outcome of well-chosen adjacencies.

Following are some adjacencies categorized by type of adjacency that can be fertile ground for foundry businesses.

Forward Integration

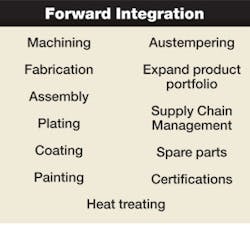

Anything adding value beyond the raw casting via additional processing or services could be considered forward integration for foundries. Heat-treating, machining, and coating are value-adding processes commonly mentioned by foundries. Table 1 provides a more thorough list of forward integration possibilities. Often the key to successful forward integration is determined by what will make the overall business more valuable in the overall OEM Supply Chain.

- Imported castings are almost always imported as machined parts;

- While many OEM’s have held onto their own machining operations, this has been a changing landscape as well;

- Machining operations are often in the position to be the Tier I or II suppliers within the OEM Supply Chain;

- The cost of machining has decreased considerably in recent years—this can change considerably the overall strategy, leading to significant cost savings in the combined casting/finishing operations.

Becoming an integral part of the Supply Chain process by adopting service capabilities that truly add value is something to consider. For example, if a foundry’s core includes an especially close relationship with an OEM, perhaps this offers an entry point to assisting the OEM in sourcing other products, in addition to castings. This might even include castings of other metallurgies or casting processes made by other foundries!

Some foundries have used forward integration to completely redefine their core business over time. Especially if the casting itself is of significant enough value in the overall OEM durable good, it’s not unreasonable to redefine the core over time. For example, a foundry making valve bodies, especially demanding ones, or high-alloy parts, could move towards making valves, then into complete fluid handling systems.

There are many fascinating examples of foundries that have made this journey. Spring City™, for example, has forward integrated from ornamental castings to become a complete supplier of ornamental lighting systems. The Water Gremlin Company has transformed over time from producing lead sinkers for fishing into a leader in producing batter terminals. Beginning as a manufacturer of couplers for fire hoses, Akron Brass Co. has transformed into a complete global supplier of firefighting systems into a wide variety of demanding markets.

Manufacturing spare parts, or wear parts, might offer another possibility of forward integrating into a service-oriented business based on field replacement of the parts. This might be developed further into a service business delivering and installing the parts.

It’s not surprising that forward integration usually offers the most fruitful ways to add sustainable, long-term and profitable growth that also can strongly protect the original core business.

Backward Integration

There are fewer opportunities that make sense for backward integration for foundries. Backing into base metal ore production or processing is not likely to succeed, although there are some examples: Precision Castparts Corp’s recent announcement to acquire Titanium Metal Corp. is an excellent one.

Other foundry groups certainly have enough critical-mass purchasing power to leverage buying key raw materials and managing commodity risk. Expertise used for managing these commodity risks conceivably could be built into revenue generating businesses in their own right.

Geographic expansion — Foundries historically have been very geographically focused, serving their surrounding region. In fact, one common way of “growing” in the foundry industry has been to acquire similar operations in other regions. Cheap assets from bankrupt businesses often have helped this process of industrial consolidation. This can be a very successful strategy for astute operators to gain critical market size and reduce overall shared costs. However, within the U.S., this “last man standing” strategy to growth eventually hits the reality of the low growth, or even shrinking domestic market.

Perhaps a more fruitful, albeit challenging, way to expand geographically is to go international. This can take the form of investing in overseas foundries to take part in the growth in other economies. Especially if this leverages and builds upon a unique and strong core, geographic expansion can offer very profitable growth opportunities. Most major casting consuming OEMs are global in scope. If a particular OEM is within a foundry’s core, this makes following the OEM internationally easier. Having a supply position in more than one major region of the world also can strengthen a foundry’s core position with the OEM in the home market.

Looking beyond the U.S. also may provide very interesting opportunities to expand product portfolios, to include other types of castings or even othExpand into other Market Sectors

Castings in aggregate represent a low-growth market, globally, and a shrinking market in the U.S. However, castings are required in practically all market sectors. The key to sustainable growth for many successful foundries is to move into new and growing markets astutely. Especially if a foundry can find and evaluate unique applications that fit well with the foundry’s core in the early part of the growth of a major new market, significant opportunities exist for profitable growth. Likewise, targeting growing castings markets might give a foundry an early indication of what could be added to its core that could be advantageous in the growth market. In the U.S., the new emphasis on oil and gas exploration and production, including new technologies for drilling, could possibly provide growth over the next decade well above historic rates for castings. Perhaps more interesting, the abundance of more cost-effective gas couldSeveral foundry operations today work to balance their sales over multiple markets in order to even out the potential impact of a down cycle in any single market. This can be especially powerful, especially if the foundry’s unique core can be leveraged well in a focused way in each chosen market.

Foundries invariably underestimate or don’t fully understand how to seek out and enter new markets. However, doing the prerequisite work to truly understand, explore, and access an emerging market is critical in entering new markets. A well-developed and detailed business development plan should be completed at an early stage, and updated often. Promising new markets must be adequately resourced.

New Capabilities

All growing businesses must add new capabilities to keep their core business healthy and to expand into new business adjacencies. It is a useful exercise to consider even these new capabilities along an adjacency axis. This helps to prioritize when, how, and to what extent new capabilities will be added, and how these will be monetized in the business. It is often best to treat a new capability as a business opportunity in its own right, even charging separately for the capability, or offering the capability as a separate business offering.

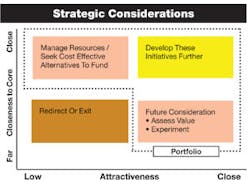

“Opportunity mapping” is an organized approach to defining the core business, then growing into adjacencies thatStrategy as a process — In applying the tools reviewed here to growth strategy, significant work is required initially. However, once completed, strategy must be implemented, which is the subject of the next article in this series. Companies that are the most successful in growth are those that can transform strategy from a singular event, to an on-going process, overlapping and supplementing their normal quarterly and annual objectives-setting and financial processes.

Mike Swartzlander is the Managing Director of Cast Strategies LLC, which provides consulting services on growth strategies to manufacturers in the metal casting, specialty chemicals, and composites parts markets. Visit www.cast-strategies.com

About the Author

Mike Swartzlander

Founder & Managing Director

Mike Swartzlander is an accomplished executive with more than 37 years’ experience and a focus on building and implementing global growth strategies. Prior to starting Cast Strategies in 2009, Mike served as Ashland Inc.’s first Managing Director in India. Previously, Mike served in a number of leadership positions at Ashland, including Vice President of Ashland Inc., General Manager of Ashland’s global castings consumables business and management positions at the company’s composites and electronic chemicals businesses. Prior to Ashland, Mike held management positions at Union Carbide Corporation and the Tate & Lyle Co. starting numerous specialty chemical businesses in the U.S., Asia and Europe.

Mike is a Past Officer of the American Foundry Society, Past President of the Foundry Educational Foundation and remains active in the industry as a speaker and author.

Mike is active in trade associations both in India and the USA, where he has been a speaker on numerous occasions and has been awarded the prestigious Ray H. Witt Management Award twice by the American Foundry Society for presentations at Casting Congresses.

About Cast Strategies LLC: Cast Strategies LLC is a trusted advisor to the global business-to-business castings, chemicals and materials industries, helping companies develop and implement robust strategies to deliver sustained profitable growth. Learn more at www.cast-strategies.com.