It’s a commonplace of late-night comedy that the average person walking the street is a) eager for attention, b) just looking for a good time, and c) hopelessly bereft of basic education. Thus, the regular feature of wide-eyed ignorance caught on camera — ostensibly for our amusement: people who cannot name the first president of the United States, mistake which nation won the American Revolution, don’t recall the date we celebrate the Fourth of July, and similar routine details of our history and culture.

There is some humor in these spectacles, though its far from original now and becomes tedious to anyone who has a serious appreciation of the past and believes there is much value in commemorating what is good, acknowledging what was wrong, and affirming the truth contained in the memories and lessons of that history. It’s more than tedium, something closer to alarm, to discover the separate impulse at large in our era by which activists and agitators seek to expunge historical facts — to declare off-limits any nominal recognition of the past because the facts therein are too disturbing to present-day sensibilities.

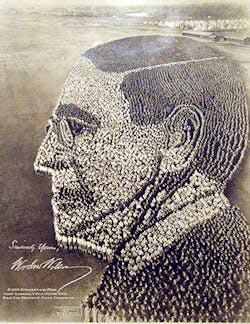

It’s common now for historical markers associated with the War of Independence, the American Civil War, the Westward expansion, and so on to be conspicuously denounced and removed to show proper deference to the particular insults felt by insistent provocateurs. Streets, parks, schools, and public buildings are de-named in order to remove from public memory any individual whose personnel file is not properly vetted to conform to modern ethics. The latest is the scolding brought to Princeton University for having so long endured the insult of building an academic venture there named for President Woodrow Wilson.

Wilson’s fate is sealed now that the nation’s most important anonymous editorial panel has taken up the cause of aggrieved undergraduates, declaring it “imperative that the university’s board of trustees not be bound by the forces of the status quo.”

I’ll not defend the former president: he was a mean-spirited and vindictive man, with a degree of vanity that is sadly common in individuals who achieve that high office. The policies he espoused were reflective of his meanness and his vanity — with one exception: he tied his legacy to a pacifist dream, and so his contemporaries found it convenient to use his memory as an emblem of that cause. As warfare became more horrific, Wilson’s reputation for idealism grew more pristine. His other qualities (for lack of a better term) were ignored because they are inconvenient to the larger purpose.

But the truth is always available to anyone who will see it. Lately, the truth about the 28th president has become too hard to overlook — but overreacting and denying him the recognition given him by his nearer contemporaries is no proper response. The likeliest result will be that Wilson’s faults will be lost to memory too. Because humans are not born perfect, bad examples teach as well as honorable ones. "Example is the school of mankind, and they will learn at no other," Edmund Burke reminded us.

Nor is the former president alone in his nonconformance to modern standards. Thomas Jefferson was a brilliant thinker – and much more, the more of which is often unbecoming to his legacy. Abraham Lincoln is a martyr to the moral foundation of American democracy, but he was personally obscure, morose, and obstinate. Mahatma Gandhi became emblematic of the cause of non-violent protest, but he also held social beliefs that less than a century later are shockingly outdated.

We cannot change the past so we must acknowledge all that is in it, defining the good and the bad, so that we may form our understanding of ourselves and our contemporaries with the best (and worst) examples available. As another calendar year closes it’s trite to recall that we have much still to accomplish – but true.

Determining to be ignorant of the truth is fitting reaction in an era when stupidity is portrayed as cleverness for entertainment’s sake. But it’s a graver error to hide facts under the pretense that they cannot influence us. Woodrow Wilson poses no threat to our present ethical standards, except in the default if we should continue building a false impression of who we are, what principles form and inform our character, and what better ideals we aspire to embrace.

About the Author

Robert Brooks

Content Director

Robert Brooks has been a business-to-business reporter, writer, editor, and columnist for more than 20 years, specializing in the primary metal and basic manufacturing industries. His work has covered a wide range of topics, including process technology, resource development, material selection, product design, workforce development, and industrial market strategies, among others.