Our recent survey of 427 Midwestern manufacturers, including 32 foundries in Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin (states that are home to just over 47% of our nation’s metalcasting capacity) revealed that many executives understand the importance of motivating their employees, but they also realize that their efforts are not particularly effective. The results of these ineffective motivational efforts are poor productivity, high turnover, bad employee relations, and a propensity for labor unrest – rather like the well-documented problems in the domestic automotive industry.

Most of the foundry executives we interviewed wanted better ways to motivate their workers. When I asked, “Motivate them for what?,” I often received a vague answer … “to work harder.” Because people costs amount to about 65% of the typical foundry’s operating expenses, anything that can be done to get that 65% to use their brains to achieve more productivity, quality, and safety will be critical to a foundry’s success. But how can this be done?

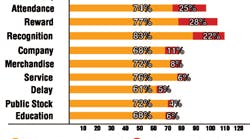

Employee motivation techniques can be divided into two categories – non-economic and economic. Behavioral scientists and human resource specialists have argued for years over which is more important — often without ever asking the workers which one may be more effective. Apparently hedging their bets, executives today apply both approaches to motivate employees.

Non-economic motivators

Non-economic approaches for motivating workers include techniques like service-award lunches, recognition aids (T-shirts, hats with company logos), preferred parking places, good attendance awards, and catalog gift items for workers achieving this or that milestone, etc.

While non-economic methods build team spirit and provide workers with a sense that management cares about their performance, the survey indicates most managers feel these efforts are of questionable effectiveness. There are two reasons for this.

First, in our permissive society, such tokens are considered entitlements. Workers expect them as their due, and resent their absence. But, the workers have little positive motivation to exceed the minimal expectations of their jobs.

Because of workers’ expectations, these entitlement programs continue with a longevity similar to government subsidies, like the payments started during World War II for hemp and beeswax production, commodities that were needed for the war effort but that continue to be supported today.

And second, because these rewards are now seen as entitlements, employees want to be rewarded for any extra efforts needed to increase productivity. Typically, their expectations for these additional rewards imply more dollars. Again, how can this be done without making the dollars merely an entitlement?

Economic motivators

Financial rewards do exist, and they can be classified according to three types:

High level — Most executives expect rewards for their performance in the form of year-end bonuses, paid for improved profitability, greater earnings per share, higher stock quotes, etc. Their pay-offs come in a mind-boggling variety of forms: stock options in public companies, phantom stock in private ones, with golden handshakes and parachutes for all. Some of these rewards have been so “innovative” that the Securities and Exchange Commission has nixed them with fines and/or prosecution, sometimes leading to a “vacation” in prison.

Low level — Many of corporate executives concluded that what is good for one is good for all, and so they have extended simpler programs to the rank-and-file employees. They realize that, like themselves, their employees want to earn more money and will respond if given the chance.

Profit-sharing plans are common. So, too, are discretionary yearend bonuses, often based on ill-defined or illusory criteria. Are they effective? Perhaps a majority of mid-level managers, a minority of first-line supervisors (up from the ranks with no training), but only a hand-full of blue-collar workers have the horizon that that help them equate what they do from day-to-day with a year-end bonus, to say nothing of a 401(k) paid out 20 years from now, on retirement.

Surely, few employees at any level refuse a year-end bonus – it’s like free money. But, when asked, most of them cannot tell you why they received the amount they did, nor can they answer what specifically they have done to earn it.

Effective ones — Effective economic motivators are transparent, easy-to-understand, and short term. They match the horizons of the workers whose behavior they are designed to affect. Today, the more astute executives I have interviewed told me that payfor- performance programs with short-term reward horizons, like Gainsharing, are the most effective ones.

Today’s Gainsharing plans reward group effort and cooperation with management to achieve company goals of higher performance, ie. more tons per hour of good castings, less scrap and remelt, etc.

Sadly, many managers think workers will rise like trout to dry flies in an effort to earn a Gainshare bonus. Because the literature on Gainsharing is widespread, these do-it-yourselfers try to design their own plans. Although there is also a lot of literature on brain surgery, few try that on their own, book in one hand and scalpel in the other.

A well designed Gainsharing plan will produce 17-22% annual improvements in productivity and costs of-quality. Good ones incorporate a combination of non-economic and economic motivational tools. Employees respond to Gainsharing’s economic motivation – the opportunity to earn extra earnings. They also respond positively to communications: when they realize they are being listened to, when their ideas are co-opted, and when they are told how their ideas are making an important contribution to their employer.

According to Dan Swartz, the president of Vancouver Steel & Iron, a leading foundry in the Pacific Northwest: “We want employees to take ownership in their jobs. By giving them the knowledge and information they need to their jobs as well as they would want, they will respond. It’s just human nature that most want to do a good job. We need to reward them for working smarter, not just working harder. That’s the key for success.”

Today, the volumes of imported castings are growing fast. Domestic foundries now struggle with excess capacity, fighting amongst themselves for the market that still exists, and emphasizing non-commodity, short-run, quick turn-around jobs. Only those with informed leadership like Vancouver Iron & Steel, working to motivate their workers to work smarter, will succeed.

| Dr. Woodruff Imberman is a frequent contributor to FM&T, having presented half a dozen reports in recent years; review his contributions at www.foundrymag.com. Imberman is president of Imberman and DeForest Inc., management consultants, and an authority on various subjects relating to manufacturing employment, including employee productivity, supervisory training, and Gainsharing and other pay-for-performance programs. Contact Imberman at [email protected]. |