In a mature global economy, as we have today, small changes have big effects. A drop in oil and gas prices can boost consumer confidence, and before very long their spending too. A shortage of semiconductors will strain manufacturing productivity within weeks. This explains why it is that in a free market, “predictability” is good for everyone; it allows individuals and businesses to coordinate resources and costs, and time in the ways that are most effective, and to embrace new choices with a tolerable degree of risk.

This also explains why for manufacturers even moderate cost savings can be impactful, for example adopting some type of automation or applying data analytics to locate inefficiencies. But when economic growth becomes more elusive, cost savings become a new sort of imperative. Saving costs overtakes improvement and investment.

In our free market we also see that small imperfections have ill effects. Certain elements in the world of finance are not content with predictability. Listening to earnings calls and reading prospectuses, one comes to understand that there is a strange attraction to the prospect of “disruption.” These investors, financiers, and executives believe they will find economic opportunities if they can force change into the normal flow of activity in an industry, a supply chain, or a business. And so, they hope to direct their influence and investments to bring that about. The disruption will be an improvement for them, because it will be a disadvantage to others.

There is a fine line being crossed. Would-be disruptors have a proper understanding of the free market and the appeal of predictability, but they view that as a problem to be overcome. They see their opportunities in the disorder that may follow once some change is announced, not in sustaining or expanding the improvements that would result from any innovation. They imagine their role in shaping the market to be more effective or efficient than actual market forces.

In literature and politics, this is called hubris. It means that those disruptors believe they are managers, not players. They believe they are outside the market, not working in it.

There is a role for change in free markets, and we acknowledge that when we highlight something for being “innovative.” Properly understood, an innovation brings a new perspective or new value to something that is established – but without changing or destroying its purpose. As such, the human qualities that promote this innovation are not disruptive or destructive but rather “creative.”

One would have to search very hard to find a market segment that is more predictable than metalcasting. Its predictability starts with the various metalcasting processes – the understanding of which has been earned by decades of practice and the experience gained thereby, and latterly confirmed by testing and analysis.

Being predictable does not make metalcasting easy or especially profitable. Reliable investors recognize its value in the fact that no one has yet imagined anything other than castings for countless applications in automotive and aerospace manufacturing, in heavy machinery construction, and in precision tools and parts production, just to name a few examples.

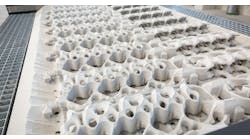

The predictability of metalcasting also does not mean it lacks for innovation. The embrace of large-scale high-pressure diecasting over the past several years is proof of the permanent value of castings for providing strength and performance, and of metalcasters’ determination to advance the possibilities of the work they do. They are creative and innovative, not destructive.

One feature of the metalcasting industry that nearly all of them revere is the personal and professional associations that they develop in the pursuit of their work. Such associations support and enhance the continuity of their efforts, and the result is something more than an industry. Metalcasting is an institution, something all too rare in the world today.

Being institutional does not mean there are no changes. There have been many in the past year. Rather it means that changes are accepted as necessary or adopted as possible, before the work continues.